Order one of our free resource packs today! Fill out the form here.

Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D

What is Hepatitis B?

Hepatitis B is a type of viral hepatitis that affects the liver. If left untreated hepatitis B can cause liver disease, cancer and death. The virus is spread through contact with body fluids, mostly blood, from an infected person.

Most people who come into contact with hepatitis B naturally clear the virus in 6 months and then get immunity from hepatitis B following that infection (referred to as an acute hepatitis B infection). 5-10% of adults do not clear the virus naturally and require treatment to manage the virus and its effects (called a chronic infection).

The British Liver Trust have a booklet you can share with people who have recently been diagnosed with hepatitis B: HBV-Just-Diagnosed-web-singles-Nov-23.pdf (britishlivertrust.org.uk)

Risk Factors

Hepatitis B can survive outside the body for at least 7 days and is 50-100 times more infectious than HIV. It is transmitted by body fluids (vaginal and seminal), and from infected blood. Risk factors for transmission include:

- Blood transfusion prior to 1996

- Tattoos or body piercings using unsterile equipment

- Sharing equipment for injecting/preparing illicit drugs

- Needle stick injury

- Un-sterilised medical or dental equipment

- Mother to baby during delivery

- Unprotected sex with someone who has hepatitis B

Symptoms

Symptoms of a hepatitis B infection include:

- Headache

- Fever

- Nausea

- Jaundice

However, 3 out of 10 people are asymptomatic, meaning they have no symptoms at all.

Testing and Results

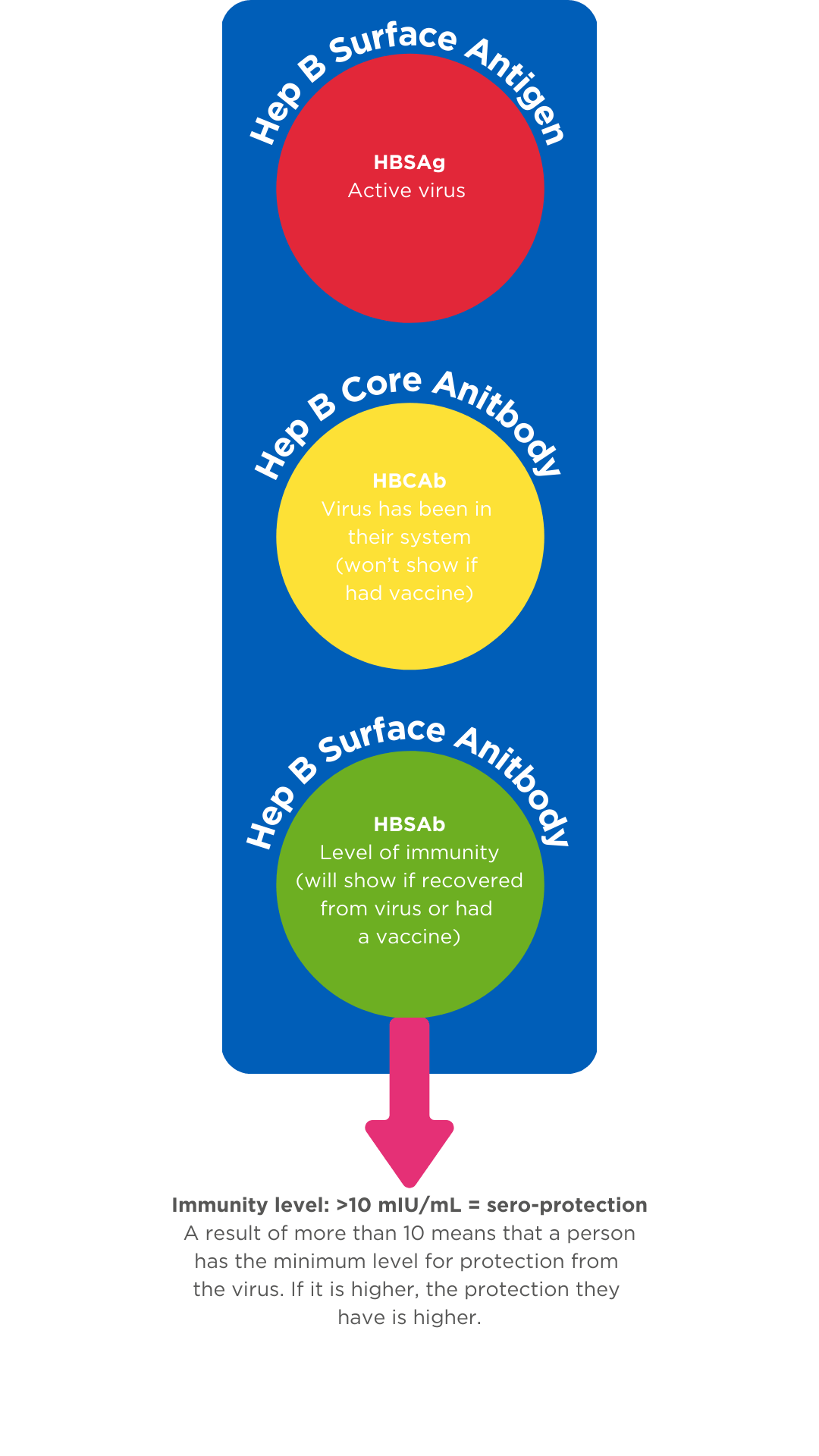

Testing for hepatitis B is simple. Normally two tests are taken (core antibody and surface antigen) and further testing would be carried out to provide confirmation. The incubation period for hepatitis B is 40-160 days therefore, if someone thinks they have come into contact with the virus it is important to test within the correct window.

Hepatitis B Core Antibody (HBCAb) – This is the test that tells you if someone has ever had the virus in their system.

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBSAg) – This is the test that tells you that someone has the active virus in their system.

If you were only testing for the core antibody (HBCAb) and the result was positive all it would tell you is that the person has been in contact with the virus at some point. Without the surface antigen (HBSAg) result you would not be able to tell if the person still had the virus or not. This is why these tests are normally completed together.

Hepatitis B Surface Antibody (HBSAb) – This tests for the level of immunity a person has to the Hepatitis B virus.

A person may get immunity to hepatitis B by either having a course of hepatitis B vaccinations, or by having the virus and the body ‘clearing’ it. Clearing the virus means that the body has fought off the infection and has produced antibodies and is referred to as ‘spontaneous clearance’.

Prevention

There is a vaccine to prevent infection from hepatitis B. It is not a live vaccine meaning there is no risk of getting hepatitis B from the vaccine itself. The vaccine’s job is to trigger the immune system into recognising the virus and producing antibodies.

Some people who are alcohol dependent or who have advanced liver disease may experience a poorer immune response to the vaccine, or if a person has kidney problems/is on dialysis they may require a double dose of the vaccine. Hepatitis B vaccines are normally administered according to a ‘schedule’. Professionals administering vaccines must follow their organisation’s policies and guidance.

The vaccine itself is maintained according to a cold chain, meaning the vaccine is not allowed to get too hot or too cold, and must be maintained between 2-8 °C. More detailed information on hepatitis B, vaccines, storage, schedules and procedures can be found in the ‘Green Book’ – Immunisation against infectious diseases: Hepatitis B: the green book, chapter 18 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Treatment

For most people who have a chronic hepatitis B infection antiviral treatment can be given which reduces the negative effect the virus can have on the body. The treatment aims to manage the virus rather than cure it. Hepatitis B treatment can help to prevent cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), liver failure and liver cancer by reducing the amount of virus exerting an effect on the body while improving liver enzyme levels.

Some people with low levels of the virus might not be treated but may still be monitored. Regular check-ups, blood tests and fibroscans are completed to review how the virus is progressing.

Differences between hepatitis B and hepatitis C

Key components of hepatitis B and hepatitis C can often be confusing for professionals. Here are some key difference between the two:

Hepatitis B

- Spread through blood and bodily fluids

- More commonly spontaneously cleared

- After spontaneous clearance gains immunity

- Preventative vaccine available

- No cure, however, treatment to manage infection is available

Hepatitis C

- Spread through blood to blood contact

- Less commonly spontaneously cleared

- After spontaneous clearance or curative treatment does not give immunity (can be re-infected)

- No preventative vaccine available

- Curative treatments are available

What is Hepatitis D?

Hepatitis D can only infect a person if they already have hepatitis B. Hepatitis D can cause symptoms which can lead to liver disease and premature death. A person can acquire hepatitis D after coming into contact with the blood or bodily fluids of someone with the virus and the transmission risks are similar to hepatitis B.

If a person has hepatitis D they may have more severe symptoms than if they had hepatitis B on its own. Symptoms can appear three weeks to two months after infection and can include dark urine/pale stools, tiredness, joint pain, fever, loss of appetite, nausea/vomiting or jaundice.

Hepatitis D requires hepatitis B to survive and therefore, if a person is vaccinated and protected by the hepatitis B vaccine course they cannot acquire a hepatitis D infection.

There are medicines available to treat hepatitis D.

Hepatitis Elimination

The World Health Organisation released the viral hepatitis elimination strategy in 2016 outlining the aim to eliminate hepatitis globally by 2030 (WHO-Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021 Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis.pdf (globalhep.org)

There are multiple examples of how services are improving the identification of hepatitis B and linking people to care, for example through Emergency Department Opt-Out Testing. Read this interim report from NHSE: Emergency department bloodborne virus opt-out testing: 12-month interim report 2023 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)